Japanese auto makers swept the U.S. market nearly 50 years ago when they introduced smaller, lighter, and less expensive gasoline vehicles to North America. After the 1970’s energy crisis Japanese industry targeted the U.S. automakers weak points, namely boat-sized cars that guzzled at the gas pump.

Overseas automakers are poised to do it again- but this time when they produce smaller, cheaper, and, pause, heavier vehicles. Electric vehicles (EVs), by design, are heavier than their gasoline counterparts. There’s an opportunity, waiting to be seized, for the automaker that introduces an electric vehicle at an affordable price, even with current technology.

Price Promises ($$):

For some time, automakers in the U.S. have promised this affordable electric car. Elon Musk said he would build a $25,000 EV, but instead switched to building the Cybertruck. Chevrolet delivered a Bolt vehicle that sold under $28,000 in 2024 but then pulled the model. This year they have a larger car, the E-quinox which lists at $33,600 but sells with higher priced options.

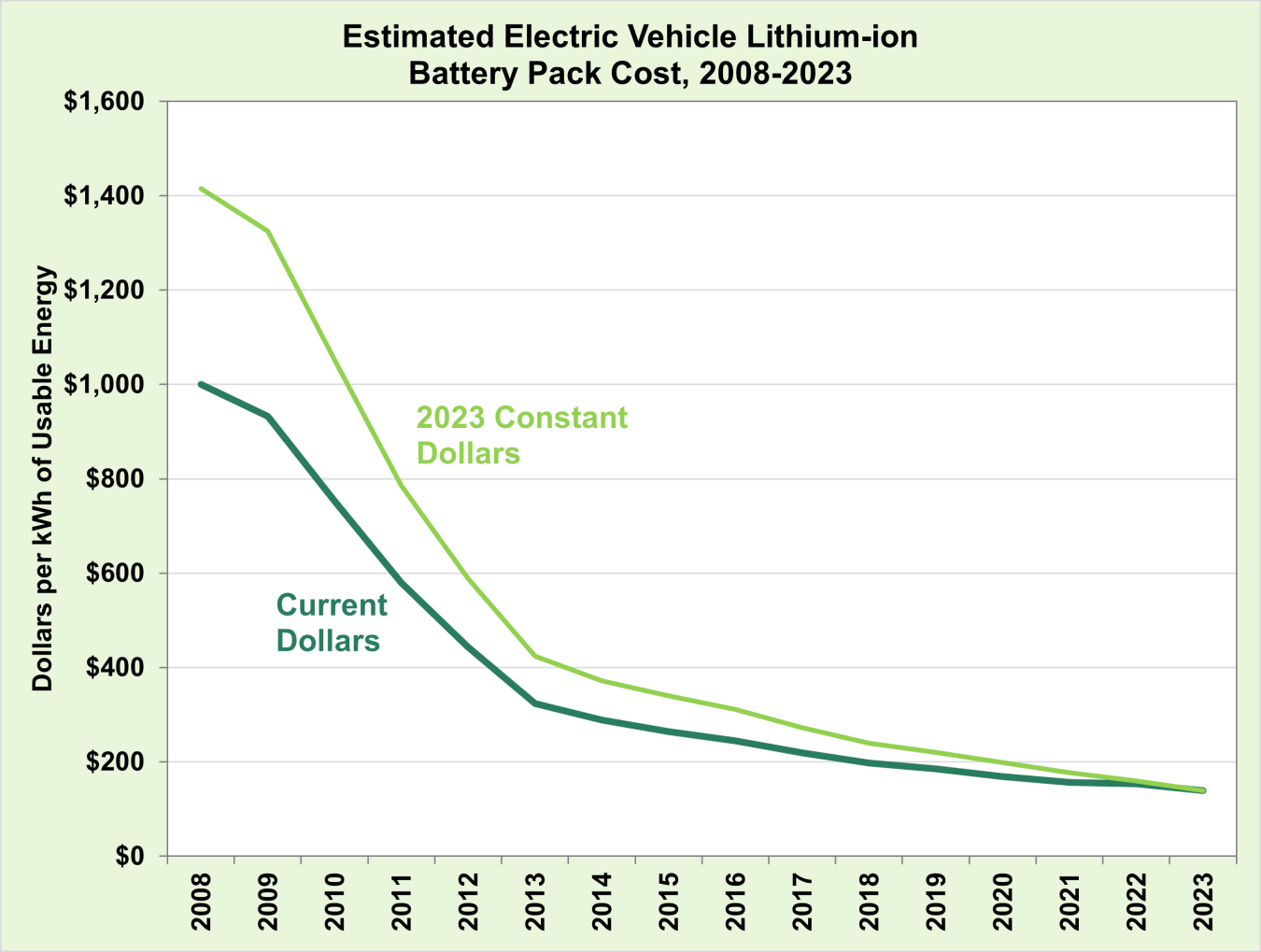

The good news is that the cost of making electric vehicles should be dropping as there are tremendous gains (i.e.: lower cost) for the substance of the car, the lithium-ion EV battery packs. There is a decline of nearly 90 percent in the battery cost between 2008 and 2023.

Per the numbers, in 2008 the cost per kilowatt hour (kWh) was $1,415 and in 2023 it was only $139/kWh. The Department of Energy (DOE) credits this to improvements in technology and chemistry, as well as to improvements in manufacturing and growth in production. Pundits compare these efficiencies to those experienced by computer chips, aka, Moore’s Law.

The Department of Energy states elsewhere on their website that their 2030 goals are to reduce EV battery pack level costs down to less than $75./kWh, maintain a vehicle range of at least 300 miles, and decrease charge time to less than 15 minutes.

Cheaper and Better:

In many ways, these DOE efficiency goals have been met and exceeded. That’s why a smaller and less expensive vehicle should be in sight. The aforementioned Chevy E-quinox, has a range that exceeds 320 miles, and under the best conditions, gains 70 miles of charge in 10 minutes. A Chinese car that is making bigger waves, the Xiaomi SU7, has a base price of $30,000 (U.S.), claims 400 + miles of range and a charge time, at the fastest Level 3, under 15 minutes. The top-of-the-line SU7 competes with the Porsche Taycan. Since it went on sale last year Porsche deliveries in China are said to be down nearly 30 percent.

This drop-in Porsche sales is waking up German automakers, and has a ripple effect elsewhere. As in the 1970s, the market is ripe for disruption. Consumers always seek smaller cars when gas prices go up, and they will probably buy an affordable electric car, when it’s smart and reliable. Producing a sports car model, like the SU7, is one thing- but there’s a substantially larger ‘everyday’ market for a compact sized, well priced, EV sedan or wagon. Perhaps it will have a smaller wheelbase- say about 106 inches instead of the hulking 120+ inches of the E-quinox and similar SUV models.

Safe too:

In the 1970s and 1980s, smaller, cheaper, and reliable were the factors that sold Japanese cars ‘by themselves’ to U.S. consumers. Electric cars bring these same features, and even more. And it’s all in the batteries- they bring even more than just a price point that is getting lower and lower.

For years Volvo has successfully touted safety in its gasoline cars. Because of their low center of gravity, EVs are safe and much less likely to roll over in an accident than gas cars. Their added weight can often help protect passengers in case of a crash by reducing the scale of the impact. Consumers will have a hard time resisting a new vehicle that is safer, priced affordably, and brings less maintenance and operating costs. And, for safety and cost, the drop in lithium battery pack price should be the winner.